High-tech orchard: Drones, sensors poised to revolutionize apple industry

GRANDVIEW — It’s 16 acres of the “apple from hell.”

That’s how Gilbert Plath of Washington Fruit and Produce in Yakima describes this plot of land devoted to growing Honeycrisp apples near Grandview.

“Every single problem in the book,” Plath said. “That’s what it’s got.”

Developed in the 1970s and ’80s by researchers with the University of Minnesota, the Honeycrisp was not bred to grow, store or ship well. It was bred for its taste, its sweetness and texture, and as tough is it can be to grow, has become one of the most widely grown — and eaten — apples in the country.

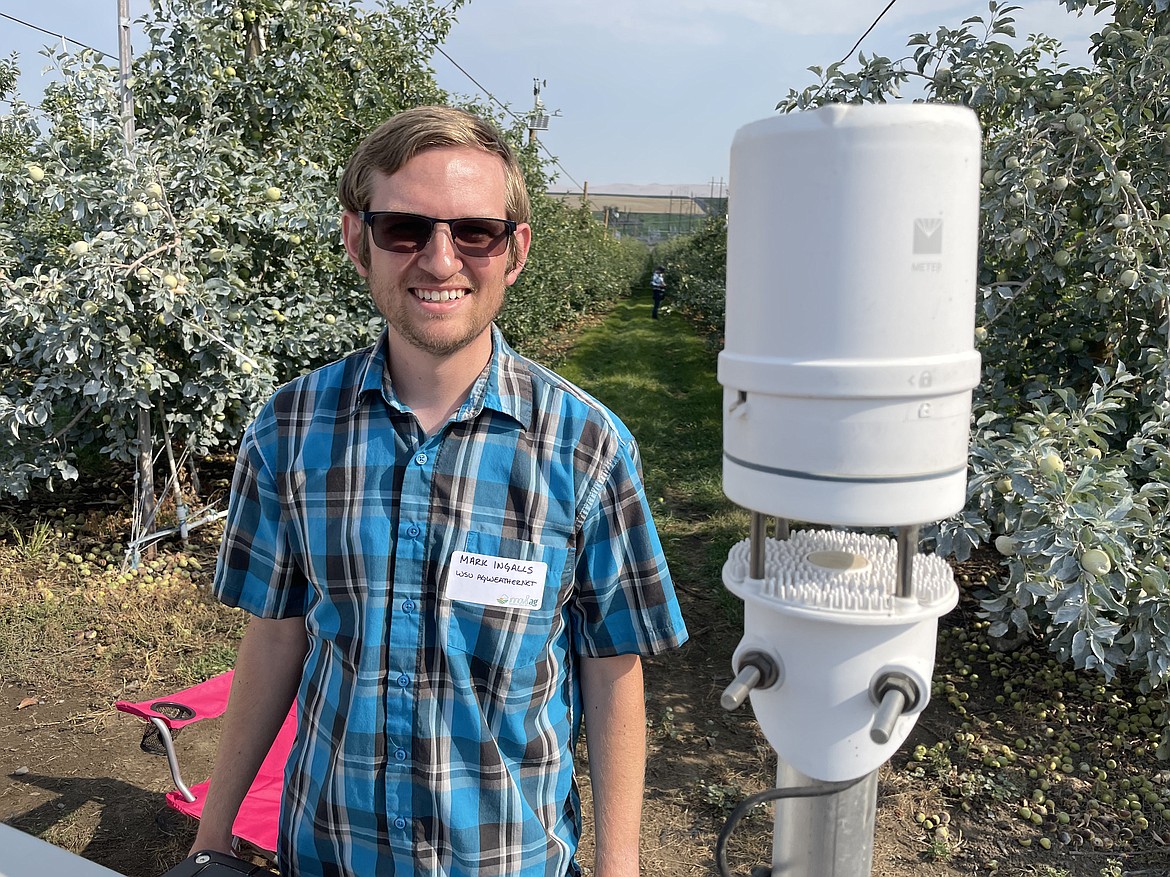

Under a hot, central Washington sun on a clear blue morning late July, scores of researchers and apple growers have gathered at the Smart Orchard in Grandview for the Smart Orchard Field Day, jointly sponsored by innov8.ag and Washington State University, to tour the 16 acres, and see what there is to see.

And that makes this orchard ideal for the second round of testing for innov8.ag’s smart orchard concept, Plath said. The first test, done last year, involved flat and consistent ground and relatively easy-to-grow apples.

It was good to prove a concept, Plath explained, that innov8.ag’s approach to getting all of the various different farm sensors to talk to each other and provide data to a single screen or app. But not all conditions are ideal — not all ground is flat, not all soils consistent, not all apples easy to grow.

“This year they said they wanted a challenge, so we gave them Honeycrisp,” Plath said. “Big problems everywhere.”

And among those problems include a north facing slope and three very different kinds of soil that require a very careful approach to irrigating the block because different soils hold and percolate water differently all while knowing some will flow downhill as well, Plath said.

“There are plenty of challenges to be had,” he said.

There’s no “one app to rule them all” quite yet, according to innov8.ag founder and CEO Steve Mantle. However, the three-year test at the Grandview ranch will not only see how innov8.ag’s technology works under tougher conditions, but will give partner companies and researchers from Washington State University an opportunity to show what they can do and how they can get all the different farm apps, sensors and technology to work together.

“The key here is breaking data silos,” Mantle said. “Most of us are here because we need to streamline and enable easier decisions, and it’s just so hard for growers to make decisions when you’ve got 10, 17, 20-plus screens open on a computer.”

Mantle said innov8.ag and its partners have placed roughly $100,000-worth of sensors across these 16 acres to measure and monitor everything from temperature, relative humidity, soil moisture, how wet leaves get to how fast apples grow and how quickly sap flows through plants.

It’s a lot of sensors.

“No grower would use that much. And that’s the point,” Mantle said.

He compared the Smart Orchard to a salad bar. No one who goes to a salad bar gets everything, Mantle said. You pick and choose what works best, to meet your needs. As growers find out what works, or what will address the problems they have, they can buy what they need.

“I think what innov8.ag is doing is something that everyone here is trying to solve the same problem,” Plath said. “So what this is going to ultimately accomplish is being able to connect different sensors together all in one, and give us some data we can act on that’s better than one sensor over here and one sensor over there, and we think this is where it’s going to be.”

Down the rows of the orchard, wide enough for one of innov8.ag’s high-tech ATVs to traverse, the soil is soggy, and mud squishes with fallen apples as you walk. The air is heavy and humid, much more humid than it is past the treelines, and smells a little of manure and barely ripe apples.

It’s in here the sensors are placed that innov8.ag is trying to bring together into one coherent data flow. The leaves can hide it, but each tree looks a little like a patient in intensive care with all the tubes, wires and devices hooked up.

WSU researcher Lee Kalscits points to a lone apple bracketed by an orange dendrometer — a curious, spring-loaded device that looks like some kind of odd finger puzzle — measuring it as it slowly grows.

“It’s digitally measuring the diameter of the fruit over time,” Kalscits said.

Every 10 minutes the dendrometer sends a measurement to the data cloud, Kalscits said, with that information compared with other data from other sensors, such as soil moisture levels and sap flow.

Kalscits said sap flow is measured by applying a heat pulse to trunk or branch, and then measuring how much time it takes for the heat to dissipate. The more water flow, the faster the heat goes away, he said.

“They’re another tool, relating all those layers together,” he said.

There are other dendrometers measuring the growth, as well as the ordinary expansion and contraction over the course of a day, of tree trunks and branches, Kalscits said.

“So we get these daily fluctuations and we actually see these responses to evaporative cooling when they run an irrigation set. It’s very sensitive,” he explained.

Two apples on each tree in this part of the orchard are hooked up to dendrometers, Kalscits explained. It gives some data, though not an awful lot, since each tree can produce several hundred apples.

Which poses a puzzle for researchers, Kalscits said. Which apples do you affix the dendrometers to?

“Part of it is accessibility, it needs to be free hanging, you don’t want any interference,” he said. “It needs to be single, in a spot where it’s not on an end branch where it’s going to get knocked off or sprayed or the wind is going to whip it off.”

That still happens, he said, and there have been times when he’s come out to the orchard to find dendrometer and apple on the ground.

There’s also another problem with a spring-loaded measurement of apple growth — the device itself can actually change the way apples grow, Kalscits said.

“So you may need to remount them,” he said.

Several rows over, Karl Wirth, a certified crop advisor with Houston-based sensor maker Dynamax, shows off a couple of trees his company has wired for data. The sap flow sensors are wrapped in reflective foil to shield them from the heat of the sunlight, and have been combined with soil moisture probes inserted to various depths — 10, 20, 30 and 40 inches deep — in rings around each tree.

Wirth said the company makes its “highly accurate and highly stable” leaf temperature sensors and its dendrometers out of Iconel, a special heat and cold resistant alloy useful in making rocket engines.

“Heat and cold don’t affect it. And we’re in an environment where you’re getting exactly that — heat and cold,” he said.

When all of this is combined, Wirth said they give a very accurate picture of just how much flows through each tree, even when minor things alter the flow of water, such as clouds passing in front of the sun.

“We can see those changes with that sap flow sensor,” he said. “And then we take that data and start making decisions for tomorrow.”

All of this data can be integrated with images gathered by drones and a pair of ATVs innov8.ag has modified with cameras, radars and other sensors in such a way that they could almost be called “farm assault vehicles.”

But it’s still a struggle getting all of the data streams, the pictures and the numbers, connected to each other.

Todd Tucker, partner with Walla Walla-based Tuctronics and sensor maker AgriNET, spent much of the morning showing off the company’s moisture probes. But he was also there to talk about the role the company is playing in innov8.ag’s smart orchard experiment as a software and app designer.

“We actually are the dashboard for innov8.ag at the current moment, though that could change,” Tucker said. “We’re the ones displaying all the third-party sensors. We knew the silo problem, and we wanted to invite third parties into our app. But that hasn’t really gone that well because everybody wants to run their own app.”

However, Tucker said farmers want something different.

“We’re trying to provide it, and it’s a challenge,” he said. “I don’t even care if we’re the one.”

But having all of these sensors, and this equipment, connected to and talking with each other is pointless if there’s no easy way to access “the cloud.” Lots of rural areas in Washington have very slow or difficult Internet access, and that’s something both Mantle and Plath say they understand and are working to address as part of the second Smart Orchard experiment.

“Connectivity is key and we’re really expanding this project,” Mantle said. “Those of you who are growers, all of you have struggled probably with some level of cell coverage, mobile coverage, internet access out in the middle of nowhere.”

Mantle said innov8.ag and WSU are working with Yakima and Tri-Cities-area internet service provider Pocketinet to provide 100 mbps (megabits per second) wifi internet access throughout the orchard.

Plath said, however, much of the data streaming from the orchard sensors is similar to telemetry from a spacecraft, and doesn’t take up much bandwidth.

“Most of the sensors are pretty small bits of data that we’re able to get out, but we also want to be able to view the data while we’re walking through the block,” he said. “And that’s what (Mantle’s) doing with the Wi-Fi signal by projecting it over the (orchard) block.”

Plath said innov8.ag is also working with Swedish cellular equipment maker Ericsson and Seattle-based venture capital firm 5G Open Innovation Lab to create a mobile cell tower system that can be deployed to farms to provide coverage for sensors, phones and computers.

Plath said they are even looking at testing the system somewhere in Grant County, where rural data access in areas where grapes and apples are grown can be spotty at best.

“That would be really exciting,” he said.

Mantle said the final goal of creating a smart orchard to bring the kind of technology to growers that have been in place in packing houses for years.

“Packing houses are highly digitized, it’s like Disneyland for apples,” he said. “They’re getting scanned, and by the time they’re through, they’re sorting everything into the right place where it needs to be, into the right cold storage.”

Mantle said it’s important to be able to follow the apple from tree to table, and the orchard is “the last frontier” to be digitized in the way that so much of food processing already has been. Packing houses will frequently make contracts months in advance to sell fruit they cannot guarantee is actually growing on trees, he said.

“I’ll be at an orchard and they will get a call from a packing house manager who tells them, ‘I need this, I don’t need this,’ and it works, but it’s super inefficient,” he said. “So streamlining that, we think, is really the holy grail we’re working toward, while saving on labor and water and so forth.”

Charles H. Featherstone can be reached at [email protected].