Developing robotic arms: More and more farm labor will be done by machines, speaker says

YAKIMA — Author Peter Zeihan has a message for Washington’s apple, pear and cherry growers.

As Mexico and the states of Central America began seriously urbanizing about 25 years ago, population growth in that part of the world began to level out and even began to decline.

Which means it’s only going to get harder to find workers for the region’s orchards and vineyards.

“That tells me that you have already passed the peak capacities attached to this region for labor,” Zeihan said during his keynote address at the Northwest Horticulture Expo on Dec. 6. “It’s not that it’s over. It’s not. But you will never get more than you’re getting now.”

The author and former analyst for Texas-based private intelligence consultancy Stratfor said while a baby boom south of the border may be possible, it’s not likely.

“The cost will never go down,” Zeihan added. “Ever.”

His suggestion?

“Bit by bit, you have to do automation,” he told his listeners.

While much of farming has already been mechanized, specialty crops such as fruit trees and vegetables still require a lot of labor to tend and harvest. However, according to Denver-based CoBank’s forecast for U.S. agriculture in 2022, the scarcity of farm workers — even with higher wages — means specialty crop producers are going to have to invest in automation.

“Agricultural labor has not been immune to the ‘Great Resignation’ resulting from the pandemic,” wrote CoBank analyst Tanner Ehmke. “U.S. fruit and vegetable acreage will continue to shift toward mechanically harvested crops that require less manual labor.”

This may explain why several companies at the Horticulture Expo’s trade show in the Yakima Valley SunDome are busily working on ways to use what are already trellised orchards maximized to expedite human harvesting and eventually replace human fruit pickers (and even, potentially, packers) with machines and automate both the harvesting and handling of fruit.

“The advantage is that it replaces people that are becoming scarce,” said Eyal Desheh, chair of the board of directors of Tel Aviv-based Tevel Aerobotics Technologies, which is developing drones to harvest apples.

He cites the costs involved to growers to obtain work permits, provide housing, comply with government regulations and pay for transportation for workers who will only legally be in the country for a few months.

It’s also hard work, harvesting apples, Desheh noted, and it’s becoming work fewer and fewer people want to do.

In fact, the United Nations Food & Agriculture Organization recently estimated the availability of fruit pickers worldwide has fallen by half during the last 20 years even as orchard production doubled.

“The idea to develop this came from the fact that fruit pickers are becoming more and more difficult to find,” Desheh said.

By early 2021, Tevel Aerobotics Technologies had raised nearly $34 million — including $20 million from Japanese farm equipment maker Kubota and Chinese fertilizer maker Forbon — to continue research and development into its drone-based fruit harvesting system.

“It’s very sophisticated,” Desheh said. “It recognizes apples, but it can pick any fruit. Stone fruit, oranges, avocados, pears. We don’t do cherries and we don’t do grapes. And we don’t do coffee.”

At the heart of Tevel’s system are four autonomous drones with cameras and driven by artificial intelligence tethered to a power source and an air compressor on a mobile picking platform. While each drone had a three-pronged grasping “hand” to start out with, Tevel engineer David Vita said that “hand” was swapped out for an air-driven suction cup.

“We had a grip, it wasn’t so good,” Vita said. “This has the capability to come from beneath, grasp, and turn and can really bring the whole apple with the stem. And it works.”

A video from a test of Tevel’s drones — which Tevel calls “flying autonomous robots” — at an apple orchard in Italy earlier this year shows two drones picking apples and putting them into bins as they make their way down a row of trellised apple trees. It’s slow work — a single drone takes an average of 11 seconds to pick an apple, Vita said, and four of them can fill an apple bin in less than an hour — but both Vita and Desheh said the Italy test, where the company was paid to harvest and orchard, showed the system functions as intended.

Now, Tevel is looking for an American partner to build a harvesting platform to base its drones on, and is tweaking the software and the AI as they deploy the system in vineyards.

“But so we’re making an adjustment as we learn,” Desheh said. “The technology is very flexible and agile.”

Under the same Yakima SunDome roof, FFRobotics co-founder and CEO Avi Kahani stands beside his giant apple-harvesting machine. It is as different from Tevel’s lightweight little drones as is possible, already integrated into a picking platform, it has 12 camera-guided robotic arms (six on each side) capable of moving to grasp apples and drop them on a soft rubber conveyor belt, which carries the apples to a bin.

Kahani has been testing his machine in Central Washington, incorporating suggestions from growers, as well as new data, and said he is “looking to have some commercial deals” in 2022. Like Tevel, Kahani said he’s not planning on selling the machine as another piece of very expensive equipment, but rather his company’s services as any orchard services firm.

“We are looking at adding additional features, like doing pruning and cleaning with the same machine,” he said. “Using this kind of approach will allow us to work the entire year.”

Kahani turns on the machine — one of two the company has built — and holds up an apple. Arms jut out and snatch at air, but none quite find the apple. That said, it’s sitting on the floor of the Yakima SunDome, surrounded by people and other pieces of equipment, and not trundling very slowly through an orchard.

“The machine is working very nice, consistently, and we are ready,” Kahani said.

A couple of rows over, Nathan Rommel — principal engineer for Ridgefield, Washington-based BTB Solutions — stands in front a giant Kawasaki-made robotic arm bolted to a shiny metal base that BTB calls a REAPR, for Rapidly Employed Automated Palletizing Robot. Rommel describes the 4,800-pound robot as “a palletizer out of a box” — and he’s happy to sell them.

“This I’ve made as a standard product,” he said. “It comes folded up. You move it with your forklift from there, you drop it on the ground, and within 30 minutes you are up and running.”

The robot arm starts moving boxes, lifting them with compressed air suction cups and gently setting them down on a pallet. Rommel says the REAPR is packed with safety sensors and has different gripping heads depending on what you might want to stack, and that it is fully and remotely programmable.

“You can call me, give me the serial number, we can remote in, and we can change all the programming,” he said. “Say you want a button in Spanish rather than English — we can change that remotely.”

This arm is the prototype, Rommel said, and he’s already sold it and a second arm for $165,000 each. With the 60-month financing plan of $3,260 per month, Rommel said the robot is about $2,570 cheaper than paying a single person $35/hour to work a full-time, 50-hour, five-day week.

“It can work three shifts for no extra charge,” he said.

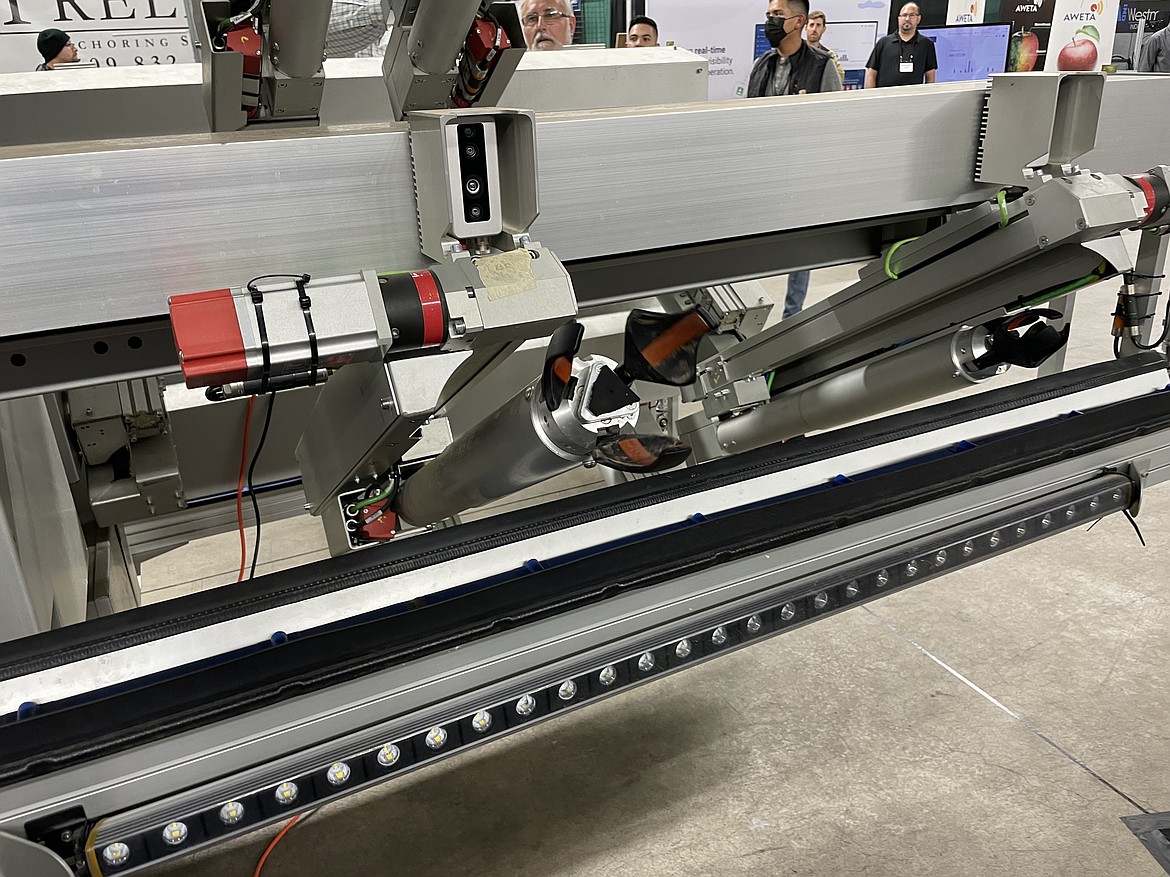

Finally, Josh Logsdon, vice president of sales and marketing for Yakima-based Haley Manufacturing, stands next to a couple of machines his company is working on. They are a robot attachment to a conveyor belt that would place cardboard top hats on fruit boxes and a much smaller version of the BTB arm that picks up pears and puts them on a tray.

The robot arm slowly hisses as it gently grasps each pear — another example of compressed air put to work to grab something.

“This is our first step into robotics. We’re predominantly known for automatic bagging equipment,” he said.

Logsdon said Haley is working with Mitsubishi Electric — makers of the robot arm — and Flexible Vision — makers of a visual AI system — to teach the machine how to recognize pears and put them in cardboard trays for shipping.

“The system is very flexible in what you can teach it,” said Henry Gomez, a senior field application engineer for Mitsubishi Electric, as he shows how the arm works. “You can teach it defect sorting, you can teach it stem and calyx location for all sorts of different fruit.”

It’s just a proof of concept, Logsdon added, showing what robotics and artificial intelligence might be capable of doing inside packing houses in the future.

“This isn’t yet a product except to say that we’re bringing these solutions together to show you what things could potentially look like,” Logsdon said. “It’s meant to spearhead ideas with folks to say, ‘Hey, where would this work, where would this be valuable, and where could this be useful as a product?’”

“It’s really a discussion point at the moment,” he added.

Charles H. Featherstone can be reached at [email protected].