Changes sought for federal hydropower regulations

WASHINGTON, D.C. — It takes an average of 7.6 years to renew the license of a hydroelectric dam, according to Malcom Woolf, the president of the National Hydropower Association.

Speaking to members of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Energy in May, Woolf noted that it took less time for Energy Northwest to renew the license of its Columbia Generating Station nuclear power plant near Richland than it took for the Grant County Public Utility District to renew the licenses on its Priest Rapids and Wanapum dams.

“It’s more complex to relicense a hydropower dam than a nuclear power plant,” Woolf said, noting that the process has taken up to two decades in some instances.

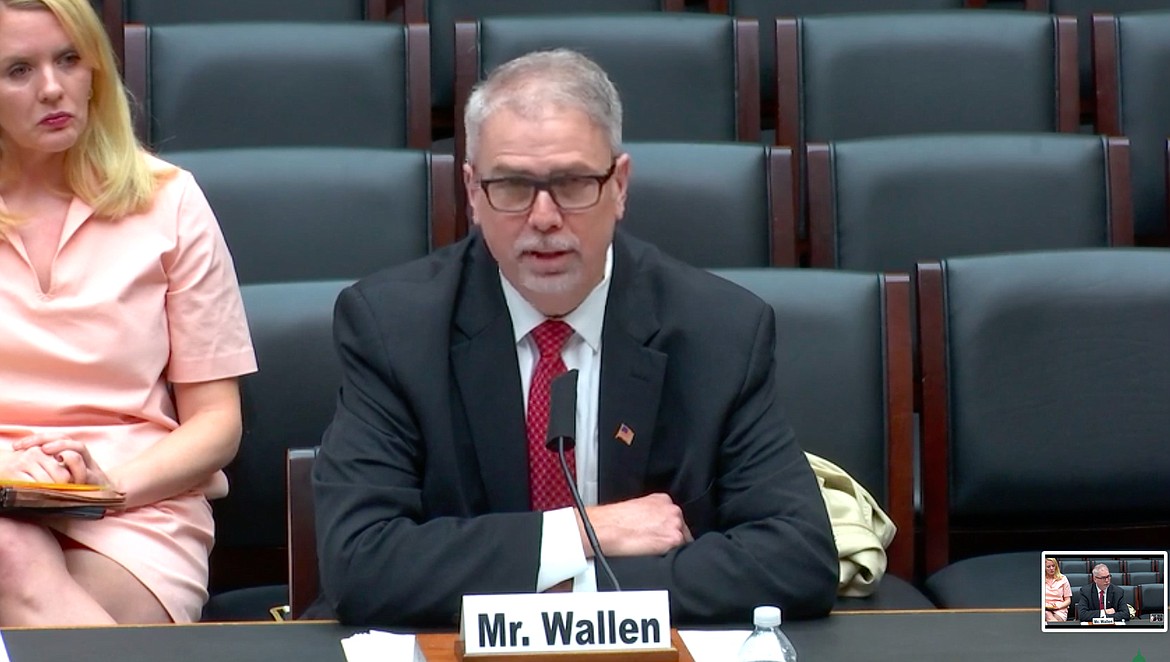

Grant County Public Utility District General Manager Richard Wallen, who was also in Washington, D.C. to testify to the subcommittee, said the PUD already relicensed its two major dams at Priest Rapids and Wanapum more than a decade ago, so any changes to the hydropower licensing process would not affect the PUD for several decades.

“We’re good at Grant until 2052,” Wallen said.

But proposed reforms that would streamline the process and put the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission firmly in charge of the relicensing process would be tremendously valuable, Wallen added, if only because demand for electricity continues to grow as more and more devices and vehicles turn from fossil-fueled internal combustion to batteries and electric plugs.

“Our load is growing, and we are approaching outgrowing physical output in 2026. We need new generation or new ways to get it,” he said. “Grant PUD values regulatory certainty. Fish and carbon-free generation all lose with an overly long relicensing process.”

According to Christine Pratt, a spokesperson with the Grant County Public Utility District, work on renewing the licenses for the district’s two big dams began in 1995, with the final renewal application submitted to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in 2005 and final approval received in 2008.

By comparison, according to information available at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s website, the NRC received Energy Northwest’s application to renew Columbia Generating’s license in early 2010 and approved it in June 2012.

“That’s way too long,” Woolf said of the process needed to renew hydropower dam licenses.

It’s an issue in a country where demand for electricity is rising, driven largely by a turn to electric-powered vehicles, the expansion of manufacturing and the increasing use of battery-powered handheld devices at the same time many governments and industries are turning to alternatives to fossil-fueled internal combustion for power out of environmental and economic concerns.

Joining Woolf and Wallen in testifying before Congress were Tom Kiernan, CEO of American Rivers, which lobbies for river restoration and is supporting calls from Native American groups to remove the Snake River dams; Mary Pavel, an attorney and member of the Skokomish Indian Tribe on the Olympic Peninsula; and Chris Wood, president and CEO of Trout Unlimited, a conservation group advocating on behalf of fisheries and anglers across the country.

While they both represent vastly different sides in the debate over hydroelectric power generation, both Woolf and Kiernan have spearheaded “Uncommon Dialog,” which has brought together both the hydropower association and American Rivers, along with representatives of Native American tribes and conservation groups, to craft a series of changes to current dam licensing rules that cut through disagreements and have the support of all the parties involved.

Kiernan’s group, American Rivers, is supporting the removal of Snake River dams as a measure to improve fish habitat and promote the recovery of rivers.

“There’s a crisis facing rivers. Biodiversity loss, climate change, racial and cultural inequity,” Kiernan said.

Wood said Trout Unlimited has a “huge stake” in ensuring hydropower is done right, and worked with Pennsylvania Power & Light to remove several dams along the Penobscot River in Maine.

“The response (by the fish) has been amazing,” Wood said, adding that remaining dams on that same river were able to make up for the lost power by increasing generation.

Wallin said the PUD has spent over $100 million on fish bypasses at Priest Rapids and Wanapum with follow-up studies showing the fish survival rate is over 96%.

Democrats on the committee were quick to praise hydroelectric power, but also emphasized the consequences to the environment and treaty obligations with Native American tribes.

“It’s a double-edged sword. It’s a wonderful source of zero-carbon electricity, but we need to reckon with the impact on rivers and ecosystems, fish and plant life,” said Energy Subcommittee Chairman Rep. Bobby Rush, D-Ill. “This is indeed a complicated issue, one deserving of this subcommittee’s attention.”

Committee member Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Spokane, said a number of industries, including silicon battery component maker Sila Nanotechnologies, are locating in Washington because the state’s hydropower is cheap, plentiful and renewable. McMorris Rodgers introduced a bill in March 2021 that would update and streamline the federal hydroelectric dam licensing process and would legally define hydroelectric power as renewable energy.

“Hydropower is vital for baseload,” McMorris Rodgers said. “It only provides 7% of national generation, but nearly half of black start capacity, so it’s more important than ever.”

McMorris Rogers also noted that every form of power generation is “a double-edged sword.”

Baseload is reliable and relatively consistent electricity generation that can provide for typical demand. Most electricity generating systems rely on baseload from hydroelectric dams, nuclear power plants and large coal-fired power plants and supplement peak demand with electricity generated by natural gas fired turbines. Black start capability is the ability of a generating plant to start up following a blackout, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s website.

According to Woolf, only 3% of the nation’s 90,000 or so dams are set up to generate electricity, and those power-generating dams only provide about 7% of U.S. electricity. However, regions like the Pacific Northwest are hugely dependent on hydropower to keep industry running and the lights on, he said. Of those hydroelectric dams, around 75% are owned by public entities – 25% by organizations like the Grant PUD and 50% by the federal government itself through the Bureau of Reclamation or the Army Corps of Engineers, Woolf said.

Woolf said he would like to see changes to hydropower licensing that would make it easier to license closed-loop pump storage systems that use electricity generated by other renewable sources – such as solar or wind – to pump water into a reservoir and then have that water flow downhill through a turbine into a second reservoir to generate power. Such a closed-loop system acts as a kind of battery, and enables forms of generation reliant on wind and sunlight to “store” potential power.

Woolf said he also wanted to see Congress make the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission — which currently licenses all hydroelectric power dams — the lead agency responsible for coordinating all other federal government agencies, involve tribes directly in the process rather than through tribal trustees in the Department of the Interior, and enact a time limit on the licensing process that begins when an application is submitted to FERC.

Pavel said it’s an anachronism in current law that, despite Congress declaring Native American tribes sovereign entities in the 1970s, when it comes to the hydroelectric dam licensing they are still dependent upon the Department of Interior acting as their legal trustee to defend the land and treaty interests of Native Americans.

“Reform would allow tribes to step into the shoes of the secretary (of the Interior Department) in regard to projects on tribal lands,” Pavel said. “It forces parties to sit down and work it out.”

Pavel said making Native American tribes and their governments direct participants in the process would shorten the licensing process considerably — a stance Woolf agreed with — citing the lengthy fight the Skokomish waged beginning in the 1970s to get their interests considered in the relicensing of Tacoma Public Utilities’ Cushman Hydro Project.

“The tribe would have been at the table with the licensee early on,” she said. “Our tribe is just a little tribe. If Tacoma would have known we were the people they needed to talk to, they would have done that.”