Harvests are up, but growers aren’t seeing the benefit

On the one hand, Washington agricultural producers are doing great. On the other hand, they’re having a tough time of it. Crop prices, generally, aren’t meeting the costs of production for most farmers and ranchers, according to the Washington State University “Washington Agribusiness Status and Outlook” report, which provides an overview for the state of Washington Agriculture.

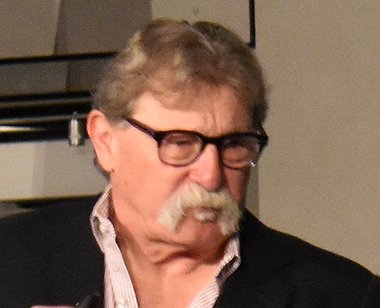

“For most commodities we grow in Washington, it’s a pretty tough year,” said Randall Fortenbery, a professor in the School of Economic Sciences at Washington State University. “We’ve had good production, but prices are quite low, with the exception of cattle prices. So, producers going forward, after their crop is harvested this year, or even dairy producers, they’re looking at some challenging prices, but some pretty good production to go along with that.”

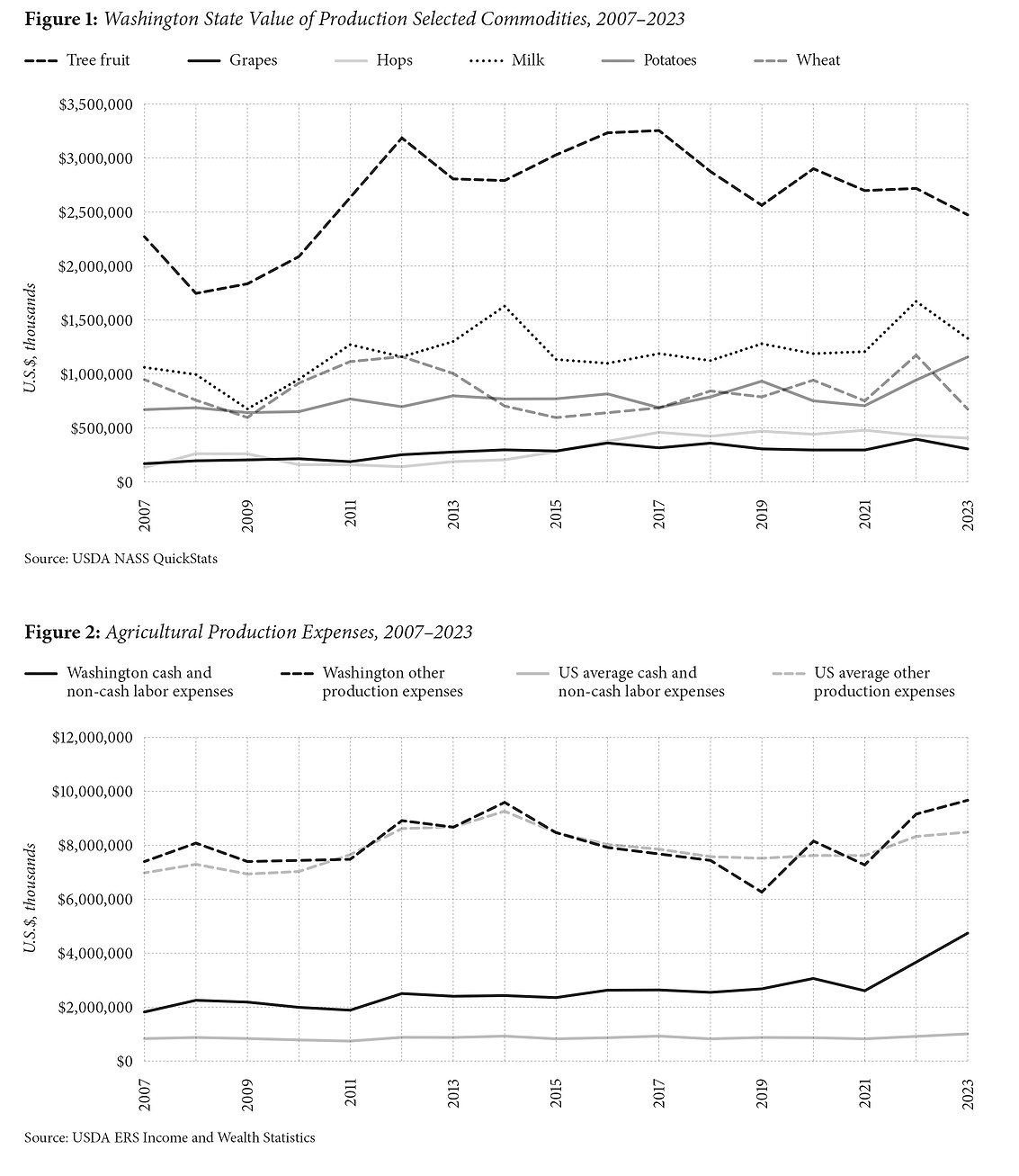

Washington grows more than 300 crops commercially, according to the Washington State Department of Commerce. The Evergreen State produce more apples, pears and cherries than any other state, and ranks second in potatoes and fourth in wheat. However, Washington is also an export-dependent state, which means the rest of the world’s economy has a bearing on the profitability seen by Washingtonians in agriculture.

Wheat is a good example of that, Fortenbery said.

“We have a pretty good crop worldwide,” he said. “It’s grown all over the world and it’s consumed all over the world. The positive is that, right now, U.S. wheat is one of the cheaper wheats on the world market, so our exports are doing quite well, but that export demand hasn’t been enough to move us to higher prices.”

The laws of supply and demand only apply so far in the case of wheat, Fortenbery said, because the demand is pretty well set.

“Wheat is consumed all over the world,” he said. “So, the only thing that really affects wheat consumption is growth in population. You don’t eat more bread when the price is lower than when it’s higher, typically, in the U.S. So, the demand doesn’t change that much from one year to the next. It’s really a supply-driven market from a price perspective, with the exception of growth in population. If there’s more people, then more wheat will be consumed. But we don’t consume more per capita from one year to the next, typically.”

Tree fruit growers found themselves in a similar position this year. Tree fruit makes up a quarter or more of Washington’s annual ag production value, according to Washington Tree Fruit Association Director Jon DeVaney. The cherry harvest this year was good, DeVaney said, but that didn’t translate to more money in growers’ pockets.

“The fruit quality was excellent,” DeVaney said. “Growers didn’t see the kind of pricing that they felt reflected the quality of the fruit they were delivering. That’s the same kind of factors that we’re seeing across the ag sector. You can deliver great quality, but you’re not necessarily getting the prices you need to meet your production costs.”

Washington’s apple harvest is on track to be one of the largest in state history, and pear production is up by almost 60% over last year at a projected 16.8 million boxes, DeVaney said. The five-year average has been about 14 million boxes, he said, but that includes last year’s 10 million-box harvest, which was unusually low.

Tree fruit is particularly vulnerable to tariffs and foreign competition, DeVaney said.

“Washington state has never been the lowest-cost place to produce things, but we’ve been able to compete in the past because we had great quality and we were able to export to developing markets that really would pay a premium for our products,” DeVaney said. “We’ve seen both tariff and non-tariff trade barriers that have made exports challenging while imports had been coming in fairly freely … China is the world’s largest apple producer, but countries like Turkey and Poland and even Iran have been producing a lot of tree fruits and competing very aggressively in a lot of markets that we have been exporting to historically.”

Potatoes, the number-one field crop in the state, are expected to hold steady, according to a report from AgWest Farm Credit. The acreage devoted to potatoes decreased by 9.4% this year, according to AgWest’s data, and prices are down $2-$2.50 for five 10-pound bags of russet potatoes in the Columbia Basin, according to the USDA National Potato and Onion Report. Washington’s potato industry relies heavily on french fry exports, primarily to Europe, according to the WSU report. Dominance in french fry exports has shifted from North America to European Union producers, and formerly minor producers China, Egypt and Turkey have increased their combined exports almost fivefold.

An outlier to the pattern is beef, which has decreased in production in Washington every year since 2019, according to the WSU report. At the same time, prices have increased at both the production and the retail levels, as anyone who has purchased hamburger at the grocery store can attest.

“The beef market is interesting,” Fortenbery said. “When prices go up at the farm level, they’re almost immediately reflected at the grocery store in higher consumer prices. When prices go down, consumer prices are quite sticky, and it takes quite a while for them to come back down. So, high consumer prices by themselves don’t always indicate strong producer prices, but right now that is the case.”

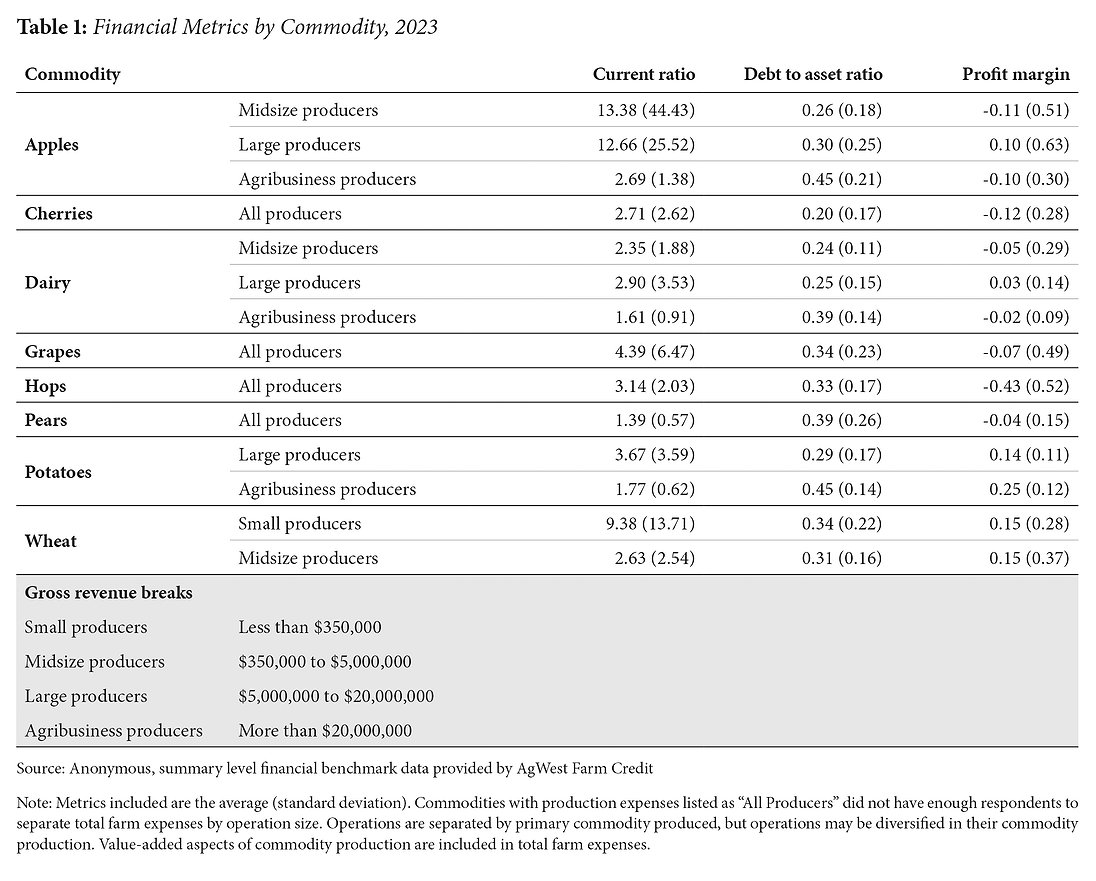

Prices may not be rising, but costs of production certainly are, Fortenbery said.

“(Growers) are facing a situation where production costs have been affected by recent inflation rates,” he said. “Fertilizers, chemicals, seed, things like that for crop producers have gone up and prices have gone down. So, the struggle is that their margins are really being challenged by higher production costs, but lower prices for the commodity that they’re actually producing. That’s their primary ulcer.”

Costs of everything from fertilizers to fuel have escalated rapidly when it comes to costs, DeVaney said. That inflation has caused economic challenges, as have labor costs which have increased dramatically, especially for manpower-intensive crops like tree fruit.

“We’ve seen rapid increases in wages required in farm labor, including shortages of workers, both because of demographic changes and other economic opportunities domestically, (and) because of changing migration patterns,” he said.

That shortage has been alleviated somewhat by the H2A guest worker program, DeVaney said, but that too is expensive for the grower. That program mandates minimum wages for the workers that are higher than the state minimum wage, to discourage growers from hiring foreign workers over American ones. Washington’s minimum wage in 2025 is $16.28 per hour, but an H2A guest worker must be paid a minimum of $19.82, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. In addition, the 2021 farm worker overtime law that took effect last year in Washington eliminated the agricultural exemption from paying time and a half for work over 40 hours a week, which impacted both workers and growers.

Fruit growers are more impacted by labor cost increases than in other fields, Fortenbery said, partly because field crops are more mechanized.

“For wheat producers, barley producers, pulse producers, it’s less of a situation because they’re not really using migrant labor and the farm labor that they’re hiring is longer-term,” he said.

The numbers aren’t adding up well for Washington farm profitability, according to the WSU report. U.S. net farm income dropped 22.6% between 2022 and 2024, according to the report. Crop receipts were expected to decrease by 11.4% between 2023 and 2024. The outlier, again, is livestock, where receipts were expected to increase by 5.9%.

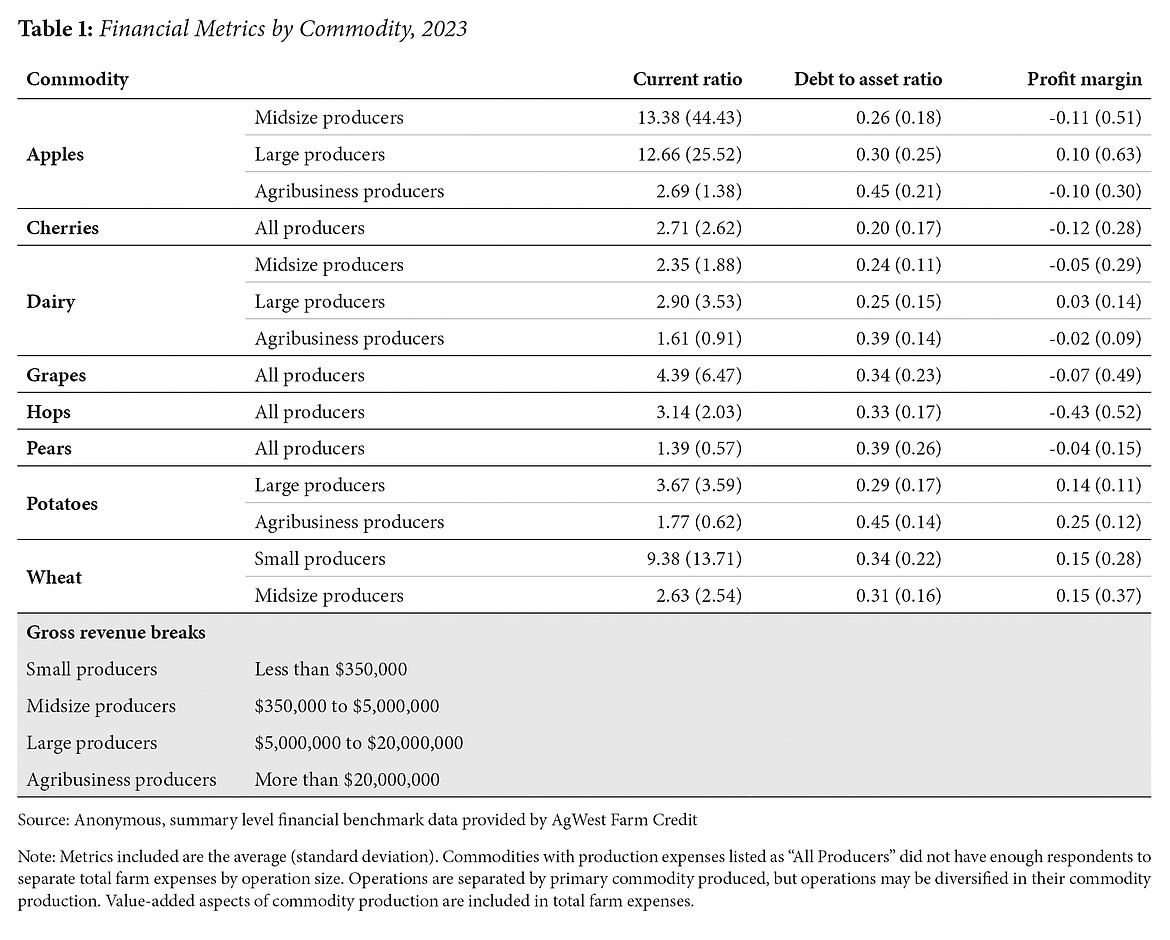

Potato and wheat growers showed positive profit margins in 2023, according to the WSU report, as did large apple and dairy producers. Small and medium-sized apple and dairy operations, as well as cherries, grapes, hops and pears, all operated at a loss.

“You can deliver great quality, but you’re not necessarily getting the prices you need to meet your production costs,” DeVaney said. “And of course, ag producers don’t have the kind of pricing power to determine that ‘This is my price. You must meet it.’”

These numbers have taken a toll on the farming industry, as growers go under and farm acreage decreases. The USDA census of Agriculture reported that Washington lost 3,717 farms between 2017 and 2022, an average of two farms a day.

“It has been really disheartening to see the amount of farms being lost in our state,” DeVaney said. “It’s not because growers don’t want to keep being growers. It’s because they’re facing a situation where they can’t sustain any further losses. If you don’t see any hope that you can continue operating without draining away the entire equity in a farm and leaving your heirs with nothing but bills, at some point you have to make the decision that you will get out of the business. And that’s not something that anyone who’s been running a multi-generational family business does lightly.”

Read the full WSU report at bit.ly/WSUAGREP.